In only one brief interview with a new product creative designer, it became clear the consumer products company was going to have significant problems with a strategic transformation. Hearing the reactions of senior leaders to the anonymous interview results only confirmed suspicions: they were on track for failure.

In only one brief interview with a new product creative designer, it became clear the consumer products company was going to have significant problems with a strategic transformation. Hearing the reactions of senior leaders to the anonymous interview results only confirmed suspicions: they were on track for failure.

It was a high priority strategic initiative to give visibility into a portion of the innovation process. It used only a part of the capabilities of a new Product Lifecycle Management (PLM) system in order to get at reducing procurement costs. Even though it wasn’t a full-blown PLM implementation, it was rightfully perceived to be a big change. So, the company spent months getting alignment to the initiative with senior leaders across the company. VPs and SVPs even had to sign off on it in a display of their understanding and commitment. Each function coughed up high potential talent to be part of the implementation team to make sure everything was set up for success. And an internationally known consulting firm was brought in for system implementation.

A month after our interview with the designer, they missed the first go-live date. Delays continued. Compromises were made. Rollout was scaled back. Soon the senior IT leader responsible for the project was gone. And so it went. What should have been a manageable but important strategic transformation led by smart, dedicated senior leaders, high potential talent, and a billion dollar consulting firm, became just another statistic in the long list of business transformation failures: broken promises, missed deadlines and budgets, and a blown ROI.

We got our first clues this was going to happen after only one interview with the creative designer. Like most others, the company was using a traditional approach to transformation implementation and change management: training. And although training is certainly necessary, it almost always proves to be insufficient.

We were reaching out to hear the designer’s point of view on another related subject and also heard something that went like this:

Designer: “We were asked to go to training for [PLM] but I told them I didn’t have time for it. Who was going to get my work done? And why should it take all day?”

Me: “How was the training?”

Designer: “They came in with a manual 2 inches thick and went through it all. I only needed to know a small part. It was a huge waste of my time.”

Me: “What was your part [of the training]?”

Designer: “We are supposed to put our designs and comments about design intent into the system. But its very confusing. [We] don’t even like Excel let alone a big system. We draw our designs and pass them on to the design engineers in the meetings and they do their part. But the [PLM] system is very scary. It looks like something for the engineers to use, not how we work.”

Turns out designers weren’t the only ones with the attitude that PLM was “not how we work”. In a few short sentences, we learned a great deal about one of the impending factors that would derail the rollout and most certainly end up being diagnosed as “resistance to change” by the implementers and “the system isn’t workable” by those who were asked to use it.

The average day for most people is full of common routines; get up, shower, grab a coffee, take the same route to work, and so on. Similarly, people form common routines in how they do their work. Soon, a significant portion of work becomes habit. And habits are very difficult to change. Even heart patients who are told by their doctor to change their lifestyle rarely do so even though their life depends on it.

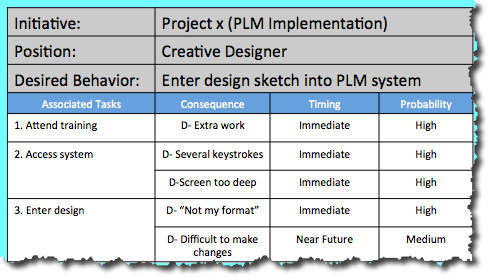

Every behavior has a consequence (see the ABCs of Behavior here). And every consequence is either positive, and thus encourages more of the behavior, or it’s negative and therefore discourages the behavior. The designer only saw and felt the discouraging consequences of using the new PLM system. It was up to the leadership to identify and implement a system of consequences that encouraged the new behaviors but instead they decided they needed more training.

Every behavior has a consequence (see the ABCs of Behavior here). And every consequence is either positive, and thus encourages more of the behavior, or it’s negative and therefore discourages the behavior. The designer only saw and felt the discouraging consequences of using the new PLM system. It was up to the leadership to identify and implement a system of consequences that encouraged the new behaviors but instead they decided they needed more training.

Typically, 75% of these initiatives fail to achieve objectives. Traditional thinking and change management is seriously broken. We need to do something about it. We need to transform our own thinking about change. Then we need to learn the tools and techniques to transform employee behaviors. And then, finally, we will begin to be more successful in transforming our businesses.